In the dynamic world of crypto, forks occur frequently, splitting a blockchain into new paths and effectively creating a new asset. Much like traditional assets, crypto transactions can carry tax implications, making it crucial for investors to grasp their tax liability. For a comprehensive overview of cryptocurrency tax, explore our UK crypto tax guide.

Throughout this article, we'll delve into the distinctions between soft forks and hard forks, shedding light on how tax should be applied to both types. Use the jump links on the left to navigate to the specific information you need.

Disclaimer

This guide is intended as a generic informative piece. This is not accounting or tax advice that can be relied upon for any UK individual’s specific circumstances. Please speak to a qualified tax advisor about your specific circumstances before acting upon any of the information in this article.

What is a crypto fork?

In the blockchain world, a crypto fork occurs when a significant part of a cryptoasset's community wants to make a change. There are two types: a soft fork, which is a backward-compatible update, and a hard fork, which creates a permanent split.

In crypto, forks happen for reasons like software upgrades, adding new features, user disagreements, or fixing security issues.

The Ethereum “merge” is one of the most well-known forks, the chain switched from proof of work (PoW) to proof of stake (PoS) offering better functionality and an optimised experience for users.

Crypto forks are a natural part of blockchain evolution, introducing new possibilities and diversifying assets. For crypto investors, forks can be both good and bad news, offering alternative investment opportunities but also bringing uncertainties and market volatility. Understanding these dynamics is key to navigating the crypto landscape. Let’s dive into the different types of crypto forks.

The different types of crypto forks

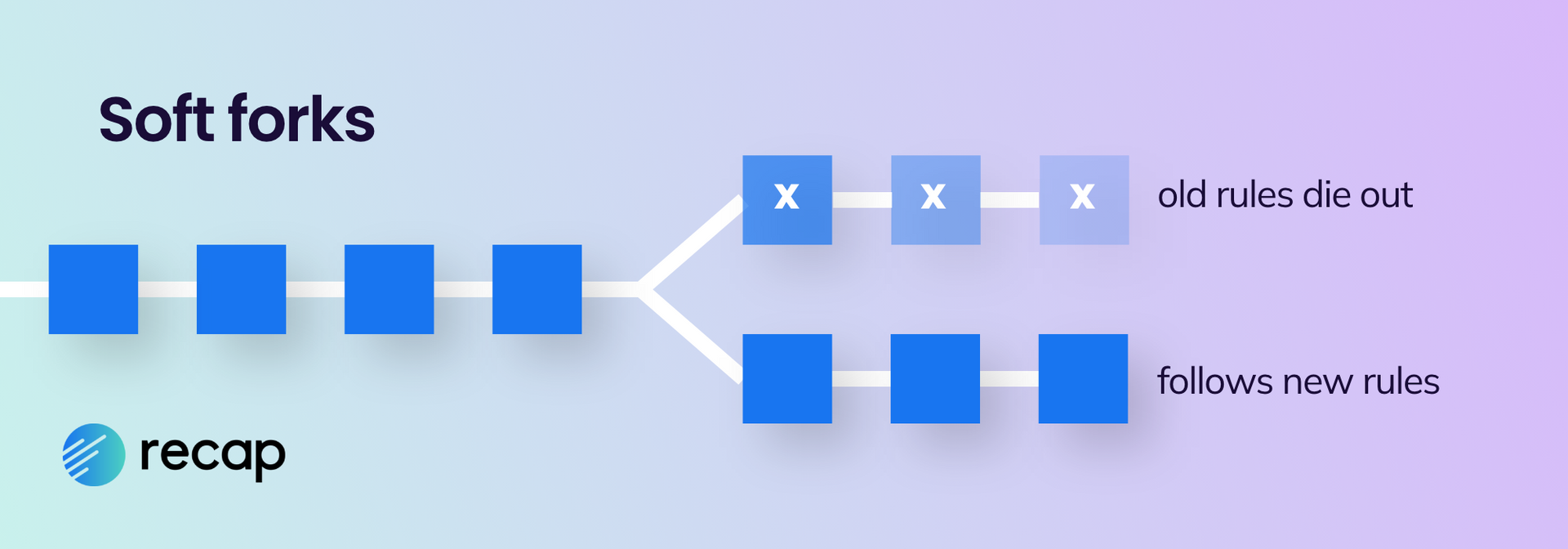

Soft forks

A soft fork updates the blockchain protocol with the intention that all participants adopt the changes. With a soft fork because users collectively agree on the modifications, the blockchain remains intact, meaning it continues seamlessly with no split and without any new tokens being created.

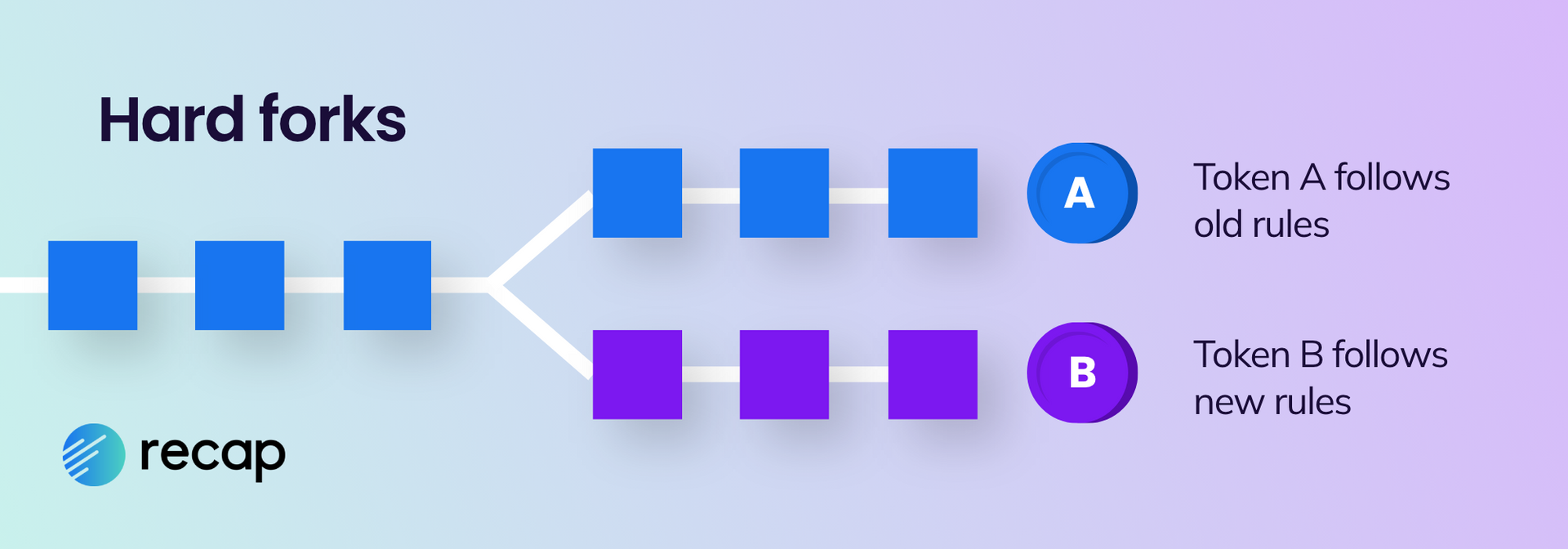

Hard forks

A hard fork involves updating the blockchain protocol, but the changes are so substantial, or obtaining consensus among all users proves unachievable, so it results in the creation of new tokens.

Unlike a soft fork, in a hard fork, the blockchain cannot persist as a single entity; instead, it undergoes a split into two separate branches - the original chain and an updated version incorporating the proposed changes. Typically, at the point of a hard fork, a second branch and, consequently, a new cryptoasset are created.

The blockchains for the original and the new cryptoassets share a history up to the fork. Individuals holding tokens of the cryptoasset on the original blockchain usually retain an equal number of tokens on both blockchains after the fork.

Is a crypto fork taxable?

The UK does not recognise a crypto fork as a taxable event, however forks can impact the future tax position of the asset when it is later sold, traded, gifted or spent.

While there might be common misconceptions circulating, such as the belief that tokens received from a fork are not taxable, particularly when you did not actively seek a fork, HMRC are clear that subsequent disposals of these tokens are subject to capital gains tax as normal. Individuals should stay informed and compliant with tax regulations, regardless of the circumstances surrounding the fork.

Taxing soft forks

In the event of a soft fork the blockchain continues and no new tokens are created, so there is no taxable event and the asset retains its original cost basis. When the asset is later disposed of by being sold, traded, gifted or spent any profit may be subject to capital gains tax and may need to be reported as part of the self assessment tax return.

Visit our comprehensive UK crypto tax guide to find out more about capital gains and filing a UK tax return.

Taxing hard forks

Similarly, a hard fork is not a taxable event however it does affect the tax position for future disposals. The creation of the new branch and new crypto asset means you now have two different assets to dispose of so you need to understand what the cost basis will be!

Up until the fork, the blockchain for the original and new tokens have a shared history. After the fork, you normally hold an equal number of tokens on both blockchains. The new cryptoassets need to go into their own pool and their value is derived from the original cryptoassets already held. Any allowable costs for pooling of the original cryptoassets are split between the two pools for the original cryptoassets and new cryptoassets.

Although HMRC does not prescribe any particular apportionment method, it is standard practice (based on the treatment of shares) that the cost of the original cryptoasset is apportioned between the old and new cryptoasset, pro-rata in line with the respective market values of each cryptoasset the day after the hard fork.

Costs must be split on a just and reasonable basis

HMRC has the power to enquire into an apportionment method that it believes is not just and reasonable. Therefore you should keep a record of this and be consistent throughout your tax returns.

If an individual holds their tokens through an exchange, the new tokens can only be disposed of if the exchange recognises the new tokens. When an exchange chooses not to recognise the new tokens then the individual may:

- seek to apportion all of the allowable costs to the original tokens (however HMRC may consider if this is just and reasonable in the circumstances)

- apportion the costs but seek to make a negligible value claim in respect of the new tokens (providing that neg value condition

Accounting for crypto forks with Recap

Calculating crypto taxes is complex and accounting for your crypto forks can be time consuming. You can make this simpler by using crypto tax software. Recap automatically classifies forks, ignoring this transaction for tax but calculating the capital gain when the asset is disposed of. In the event of a hard fork, Recap applies an accurate valuation to both the new and original tokens. Get started with Recap for free!